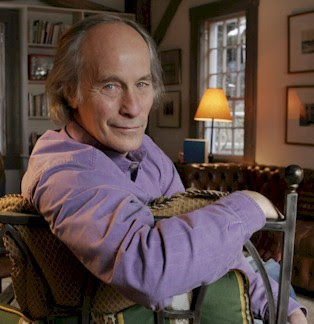

Richard Ford ornitólogo

¿Cuánto sabe un pájaro de ornitología? Esa es la pregunta que muchos se hacen cuando ven a un escritor teorizar sobre literatura. Concretamente, Jakobson usó la metáfora (ligeramente más ofensiva, no dijo pájaro sino elefante) para impedir que Vladímir Nabokov consiguiera un cargo universitario mejor remunerado. Pero leer las lecciones de literatura de Nabokov representan para quienes queremos aprender el oficio una experiencia insuperable. Lo mismo podría decirse de este texto de Richard Ford, un fragmento de un texto que se publicará en Granta, que aparece en The Guardian y en el que comenta -a partir de la lectura de un cuento de "La dama del perrito" de Chejov y "Reunión" de John Cheever- el ejercicio de la autoridad en la escritura de los textos breves. Imprescindible.

Dice Ford: " "Really, universally, relations stop nowhere ... the exquisite problem of the artist is eternally to draw, by a geometry of his own, the circle within which they shall happily appear to do so." Henry James, here, is commenting on art's abstracting-coercing relation to lived life when performed by the hand of the artist. James's "geometry of his own" is the restrictive, importance-making exercise of (in the case of writing fiction) the writer's authority - as expressed by such authorial decisions as how much of this character to reveal, when to end a scene, where to commence the story and where to stop it. When John Cheever's narrator, at the astonishing conclusion of his brief but harrowing story "Reunion" - published in the New Yorker in 1962 - bluntly tells us, "And that was the last time I saw my father ...", we readers feel the story's "geometry" fiercely close down. We have known Cheever's two people - a father and son - for only a page or two and not well, we think. Can it really be, though, that the son never sees his father again - ever? We would surely wonder about this in real life and demand to know more - require a novel to explain it all. But the story doesn't entertain doubt and neither do we. Relations in life may, indeed, stop nowhere. But in the hot alembic of the story's manufacture they do. Cheever's story is a model of short-story virtue, focus and conciseness. In fewer than a thousand words we visit Grand Central station twice, enter and depart three distinct midtown eateries. Cocktails are consumed, harsh, assaultive even hilarious words are exchanged, tempers burn hot, dismay turns toxic. A callow son's hopes for resuscitating the love of his father are summarily ruined, following which a vital part of life is over for ever. Only, life's not like that - we say again. At least ours isn't - we hope. Yet within Cheever's great authority something of life we couldn't know any other way and that can't be truly paraphrased is shaped into indisputable truth for which the story is the only testament and evidence. Moreover, this ferocity and concentration of the story's formal resources (its formal brevity, dramatic emphasis, word choice, sudden closure) are aesthetic features we readers like being close to, and submit to with pleasure - if only because these events aren't really happening to us. And while saying this much may not tell us precisely why "Reunion" is so dazzling, it begins to suggest importantly how. And our awareness of this how may please us, too. Nothing, in fact, may tell us definitively why any story is excellent. Cheever's story is about a father and a son in an instant of defining, galvanising crisis - the dramatic and moral values are thus set up high (always a help). The scene and settings are recognisable, vivid and deftly limned. It's extremely funny, albeit in a hateful sort of way. A risibly mean and pathetic drunk is given his (to us) satisfying comeuppance, while a sweet-seeming, impressionable son survives to tell the tale. Bliss is once again moved revealingly into the orbit of bale, all of it delivered inside a streamlined little verbal torpedo that explodes upon us almost before we know it.

Etiquetas: cheever, chejov, eeuu, inglaterra, NOTICIA, richard ford, rusia

» Publicar un comentario