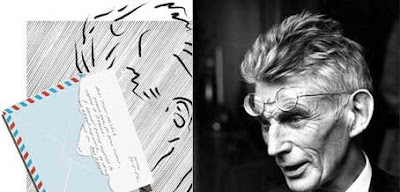

Las cartas de Beckett

La editorial Cambridge University Press ha publicado el primer tomo (de tres que vendrán) de la correspondencia de Samuel Beckett. En The New York Times el encargado de dar la noticia ha sido Joseph O’Neill, autor de la exitosa novela Netherland, quien anuncia que el huraño autor irlandés de obras parcas y descreídas como Esperando a Godot se convierte aquí en un corresponsal frágil y amable:

Beckett, in his published output and authorial persona, was rigorously spare and self-effacing. Who knew that in his private writing he would be so humanly forthcoming? We always knew he was brilliant — but this brilliant? Just as the otherworldliness of tennis pros is most starkly revealed in their casual warm-up drills, so these letters, in which intellectual and linguistic winners are struck at will, offer a humbling, thrilling revelation of the difference between Beckett’s game and the one played by the rest of us. (Beckett played tennis, incidentally.)

Por otra parte, O´Neill también cita algunas reflexiones personales del autor sobre su familia, su época (la Segunda Guerra Mundial), la mujer que amó:

Although there are no letters here to his parents — perhaps because Beckett authorized the publication only of letters “having bearing on my work”? — there is no doubt he remained deeply preoccupied by “the fading fact of my family.” He notes: “Lovely walk this morning with Father, who grows old with a very graceful philosophy. Comparing bees & butterflies to elephants & parrots & speaking of indentures with the leveler. Barging through hedges and over the walls with the help of my shoulder, blaspheming and stopping to rest under color of admiring the view. I’ll never have anyone like him.” Several months later, the father dies. The son says, “I can’t write about him, I can only walk the fields and climb the ditches after him.” This bereavement was, no doubt, one of the events that influenced the progressive calming, over the years, of Beckett’s tone. About the possible Nazi invasion, he writes from Paris: “No matter how things go I shall stay on here. . . . All I have to lose is legs, arms, balls etc., and I owe them no particular debt of gratitude as far as I know.” There is little sign, in these pages, of sustained attention to political and economic crises. The Great Depression is not mentioned, and Hitler and his cronies figure, briefly, as absurdities; even when he travels in Nazi Germany in 1936-37, Beckett’s focus is on galleries and churches. The future member of the Resistance has yet to show himself. In June 1940, he writes from Paris: “Suzanne seems to want to get away. I don’t. Where would we go, and with what?” Suzanne is Suzanne Deschevaux-Dumesnil. Here’s how we learn of her: “There is a French girl also whom I am fond of, dispassionately, and who is very good to me. The hand will not be overbid. As we both know that it will come to an end there is no knowing how long it may last.” Beckettists will know, of course, that in due time Suzanne and Sam married, and that the marriage lasted till their deaths.

Pueden encontrar un comentario en español a la nota de NYT en la revista Ñ.

» Publicar un comentario